- Home

- Orania Papazoglou

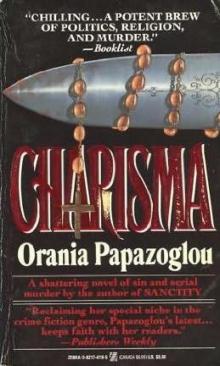

Charisma

Charisma Read online

Charisma

Orania Papazoglou

A MysteriousPress.com

Open Road Integrated Media

Ebook

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Chapter 2

1

2

3

4

Chapter 3

1

2

3

Chapter 4

1

2

Chapter 5

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Part 1

Chapter 1

1

2

Chapter 2

1

2

3

Chapter 3

1

2

3

Chapter 4

1

2

Chapter 5

1

2

Chapter 6

1

2

3

Chapter 7

1

2

3

4

5

6

Part 2

Chapter 1

1

2

Chapter 2

1

2

Chapter 3

1

2

Chapter 4

1

2

3

4

Part 3

Chapter 1

1

2

3

4

5

Chapter 2

1

2

Chapter 3

1

2

3

Chapter 4

1

2

3

Chapter 5

1

2

3

4

5

Part 4

Chapter 1

1

2

3

Chapter 2

1

2

3

Chapter 3

1

2

Chapter 4

1

2

3

Chapter 5

1

2

3

Part 5

Chapter 1

1

2

Chapter 2

1

2

3

Chapter 3

1

2

Chapter 4

1

2

3

4

Chapter 5

1

2

3

Part 6

Chapter 1

1

2

Chapter 2

1

2

3

Chapter 3

1

2

3

4

Chapter 4

1

2

3

Chapter 5

1

2

Chapter 6

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Epilogue

1

2

3

Prologue

Chapter One

1

HE WENT TO MASS that morning—seven o’clock Mass for the first Sunday in Advent, with the pink and purple candles rising from a nest of leaves at the side of the altar and the priest singing the preface in plain chant. It was a church he didn’t know and a priest he had seen only once or twice before. The priest had never seen him at all. Still he thought it would calm him if he received Communion.

Outside it was a cold dark morning in early December, one of those days when it seems the sun will never rise. The wind blew sleet against the stained-glass panes of the windows along the church’s north wall. The air-lock door in the foyer wasn’t working properly, and blasts of cold came in with every late arrival. The church was filled with old women and couples with very young children. This was the Mass for people with something to do with the rest of their day.

He, too, had something to do with the rest of his day, but standing for the Lord’s Prayer he could forget about that. What he couldn’t forget about was the church itself, which was old and filled with statues. It was a small parish tucked away in a forgotten corner of the city. He thought the bishop had to be ignoring it. God only knew, the order to “simplify” had not been heard in this place.

When it came time for Communion, he slipped into the aisle behind a nun in a habit that made her look older and fatter than she was. He took Communion in the hand and walked back to his pew chewing vigorously. Chewing the Host was one of the revenges he took against Sister Mary Mathilde—who was probably dead and in Hell and watching his every move. He didn’t take a lot of revenges against Sister Mary Mathilde. He recognized it was childish.

When he knelt down for his Communion thanksgiving, the knife in the pocket of his jacket knocked against his chest and he was brought up short. It was only for a moment, but it made him feel like an amateur. And that was bad. The one thing he had never wanted to be was an amateur anything.

The priest went back to the altar and began the prayer after Communion, slipping into plain chant again as if it were a habit he couldn’t break. The sound was lulling but not really effective. Now that he had felt the knife once, he seemed to feel it all the time. The floor under his feet felt very hot, the way it would be if someone had lit a fire in the basement.

He stood through the Concluding Rite in a fog, wondering what in God’s name he was doing in a church.

2

The parish was not only small but very old-fashioned. Its members lived in double-and triple-decker houses on the streets immediately around it, leftovers from a time when this city had been a Catholic stronghold and a seed ground for vocations. Now the neighborhoods that bordered this one were black or Hispanic or just plain bombed out. There was a crack house a block away from the rectory, and a chop shop for stolen cars across the street from the apartment where Mrs. MacGerety lived with her ninety-year-old mother. The United States Supreme Court had put an end to the crèche that had once stood in the small public park all through Advent and Christmas. The drugs had put an end to the crowds of children that had once choked the crosswalks on their way to and from the tiny parish school. This whole section of the city was in a state of religious civil war: church people against crack people, Christians against nothing-at-all. Even the Workingman’s Club, that Depression-era fortress of proud atheism, had put mangers and angels on its windows for the season.

He left the church before any of the rest of them and stood at the bottom of the steep marble steps, looking up at the blank faces of the houses around him. He was not afraid, but he could feel the wrongness of it. Everything here, even the church, was already dead—and it had been murdered. That was what he thought of to describe it. It made him feel instantly better. He wasn’t losing his grip on things after all.

He waited until the rest of them started to come out and then moved away. He turned down a side street he had never been on before and looked at the statues of the Virgin on the tiny front lawns. This close to the church, everyone was Catholic a

nd everyone was poor. The neighborhood was a great square marked off for half a dozen games of tic-tac-toe. He was in no danger of getting lost.

He made a turn and then another turn and then another turn again. When he had done all that he found himself in front of a tall green triple-decker with a dove-of-peace plaque on its worn front door. The plaque was hung inside the glass, to save it from being stolen. He looked up at the windows of the second- and third-floor apartments and saw that they were dark. He was beginning to wonder if they were abandoned. He’d been in the groundfloor apartment four or five times already, and he had never heard a sound above his head.

He waited anyway, for caution’s sake, while the rumble of distant traffic made him think about storms. They had cut a highway through the deserted neighborhoods half a mile from here. The highway was always full of tractor trailer trucks. He started to get itchy, and moved to relieve himself. The lock on the back door was solid, but the locks on the windows were useless. He broke a pane of glass and climbed inside.

Three blocks away, the church started ringing its bells. It was eight o’clock in the morning, and he was very cold.

3

Fifteen minutes later, she turned onto the street: the woman who lived in this apartment. She was a more-than-middle-aged woman with a body rapidly melting into shapelessness and a round, oddly innocent face, one of those “good Catholic women” who baked cakes for the rectory and looked after children whose parents wanted to go to Confession. At Halloween, she put laminated pictures of the Sacred Heart into little orange-and-black bags full of candy corn. At Christmas, she bought hand-painted cards from the Benedictine nuns and sent messages that said “May the joy of Christ be with you all this season.” Once, every parish had had a hundred women like her. They came to every seven o’clock Mass and every parish Rosary and every Fatima novena. Now they were mostly gone, to the suburbs or the grave, and nobody knew why this one was still around.

But he knew. He watched her come up the street, stopping every once in a while to rub the joints of her fingers where her arthritis bothered her. He knew this woman very well, even though he had spoken to her only once. Her name was Margaret Mary McVann. Every Monday afternoon she served lunch at a soup kitchen two parishes away.

She stopped at the wrought-iron gate, rubbed her hands again, then pushed the gate open and came inside. He was standing just inside the door, one of his arms brushing against the curtains that covered the living-room window that faced the street. He was cold. The window he had broken had dropped the temperature in this apartment to something close to freezing. She started to come up the steps. He held his breath.

Damned idiot, he thought. He didn’t know if he meant Margaret Mary or himself.

She let herself into the vestibule, fumbled around for a moment at the bottom of the stairs, and then put the key into the lock of the apartment’s front door. He held his breath again. When the door swung in, he went rigid.

In the silence, the cuckoo clock on her kitchen wall sounded maniacal.

4

He had laid her things out on the coffee table, all her religious things from when she had been a nun. There was no habit—they were never allowed to keep their habits—but there was a fifteen-decade rosary and a heavy brass medal and the leather-bound copy of the Little Office she had been given when she entered the novitiate. There was even a picture: three nuns in old-fashioned habits, all of them very young and all of them smiling. On the back of it someone had written, “Sisters Ruth, Peter and Innocentia—in Rome!!!”

He had meant to lay out the rosary he had sent her, but he hadn’t needed to. It had been on the coffee table when he came in.

5

She came through the door and stopped, staring at the things on the table. He was still behind the door, so he couldn’t see her. He did hear her. She sucked air and reached automatically for the holy water font on the wall just inside the door. She crossed herself and started saying the Hail Mary.

The rosary he had sent her was made of real amber. It glowed oddly in the not-quite-light that came through the living-room curtains.

He had the palm of his hand flat on the door. He pushed the damn thing shut and it slammed. That was when he felt himself losing it.

6

Damnherdamnherdamnherdamnherdamnher, he thought. The blood rushed into his head. Something inside there was getting bigger and bigger and bigger, pushing against his skull, making him blind. He kept thinking of amber as a death trap: prehistoric insects caught and suffocated, drowned in glue, petrified. He kept thinking of dinosaurs stripping the leaves from trees and leaving behind them barrenness.

Damnherdamnherdamnherdamnherdamnher.

She turned toward him and put her hands to her face. He saw her skin go white and her eyes grow larger.

7

When she saw who and what he was, the panic drained out of her and the confusion began, raw confusion like the addledness of someone who has woken up in the middle of a dream. She hesitated, seeming to want to come toward him. He came toward her instead and she stepped away.

He got one hand around her jaw and the other on her shoulder. He dragged her to him and spun her around. She got a hand inside his jacket and pulled.

He tore her neck just as she tore his jacket. The sounds were strangely similar.

A moment later, she was on the floor, dead.

8

The blood drained from his head and his eyes cleared. She had a piece of his jacket lining in her hand. He took his jacket off and left it folded over the back of a chair. He was wearing two sweaters over a shirt and undershirt. He’d survived like that before in the cold. Besides, it had never really been his jacket anyway.

Somewhere outside, the church bell rang again, a single solemn gong marking the half hour. It had taken no time at all. He hadn’t been too weak for it. He had only to worry about finishing up, and about the weather. He hadn’t noticed it before, but the sky had opened. There was snow coming down as thick and fast as summer rain. Through the crack in the curtains he could see it piling up on the dead branches of the yard’s one tree.

He picked up her nun things and put them back in the drawer where she’d kept them, the third one from the top in her bedroom bureau. He went back into the living room and rescued the knife from his discarded jacket. The rosary he had sent her was still on the coffee table. It had been jogged out of place. It looked as if she’d been saying it and then put it down, carelessly; on her way to do something else.

The cold was still slipping through the window he had broken, dropping the temperature lower and lower, making everything frigid.

9

She was lying on the floor with her head tilted too far around, with her legs spread apart as if someone had tried to rape her. But he hadn’t tried to rape her. He didn’t want to rape her. She was an old woman. Sex had never held much interest for him anyway.

10

What he really wanted to do was cut.

Chapter Two

1

SOMETIMES, SUSAN MURPHY THOUGHT her life would have been easier if she had been able to look at it as a series of grievances. God only knew, her history entitled her to one or two. Standing in this stone-floored foyer, looking out at a landscape she had once known more intimately than she had ever wanted to know anything, she could count out the things that would have turned any of the women she knew into raging shrews. Her father, her mother, her order, her Church: Dena, who had been a Franciscan before the ravages of Vatican II, would have taken any one of these things and run with it. In fact, she had. The last Susan had heard, Dena was down in South America somewhere, trying to bring contraception to women who only wanted to know how to have more babies, and communism to farmers who had their minds on jungles and rainfall.

One wall of the foyer was a great glass window, leaded and paned. Susan looked out of it at trees and rocks and curving stone walls. It was a beautiful place, Saint Michael’s. Its fidelity to the spirit of the medieval Church was absolut

e. So was its fidelity to the spirit of nineteenth-century capitalism. What it reminded her of, more than anything, was home the way home had been before the real trouble started: that massive house on Edge Hill Road; that endless dining room with its forty-chair table set with silver; her mother in pale pink taffeta and too many pearls. One of the reasons she was leaving the convent was that too much had started to remind her of home as home used to be. Sometimes, waking up in the morning and not quite rid of sleep, she thought of herself not as Sister Mary Bede, but as the woman her mother had once told her she would be. What scared her was the possibility that that woman was what, in spite of everything, she really was.

Silly ass, she thought. She heard sounds above her head, heavy shoes on wrought-iron spiral stairs. She looked up to see Reverend Mother coming down to her, moving painfully, stopping on every riser to catch her breath. The black folds of an only-slightly-modified habit shifted and swirled in the air around her, making her look like a moving cloud.

“Are you all right?” Susan said.

“I’m fine.” Reverend Mother came down two more steps, stopped, and sighed. “If you wouldn’t wear a jacket, you could at least have let yourself into the office. There’s no heat in that foyer.”

“I’m not cold, Reverend Mother.”

“Of course you’re cold. Everyone’s cold.”

Susan started to fold her arms under the short cape of her habit, realized it wasn’t there, and stuck her hands into the pockets of her jeans instead. The jeans were new, and stiff. They scraped against the skin of her legs and made her wonder if she was bleeding.

It was seven o’clock on the morning of the Monday after the first Sunday in Advent, December 2. She had just spent half an hour in this foyer, trying to be angry. There had been days lately when that was all she ever did.

She crossed the foyer and opened the door to Reverend Mother’s office, mostly to give herself something to do. Then she let herself slip into her favorite fantasy.

She was driving along the road somewhere, sliding through small towns full of small stores and twenty-five-dollar-a-night hotels. The snow was thick and absolutely white, just fallen. The thin branches of the trees were encased in ice, so that the trees looked decorated. The sun was shining.

Charisma

Charisma