- Home

- Orania Papazoglou

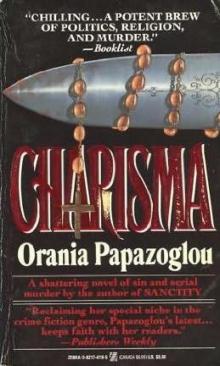

Charisma Page 2

Charisma Read online

Page 2

Up ahead, just coming into view, was a wide open Dunkin’ Donuts.

2

The meeting in Reverend Mother’s office was a ritual, like Mass. Every nun who left this order had to have one, even if she left before Profession. Susan had never understood what for. In her case, at least, there was nothing unexpected or inexplicable. She and Reverend Mother had been talking it over for months.

Of course, it was hard to pin down what they’d said to each other, or what they’d understood. Susan decided she was here because she was supposed to be here. To have left any other way would have been rude. Neither Sister Mary Bede nor the Susan Katherine Murphy of Susan’s mother’s fantasies would ever be rude.

She sat down facing the oversize crucifix at Reverend Mother’s back and stretched out her legs. She had to, because she found it hard to bend them. Her brother Dan had sent her the jeans. She had sent him her measurements. He liked clothes tighter than she did.

Reverend Mother poured two cups of coffee from the pot on the tray Sister Martina had brought in and handed her one.

“Did you get it all straightened out about the car?” she said. “I heard you on the phone last night. What makes them think nuns have credit cards?”

“They don’t think nuns have credit cards, Reverend Mother. They just don’t rent cars to people who don’t.”

“There probably are nuns who have credit cards,” Reverend Mother said. “Out there, somewhere.”

“Out there, somewhere” was Reverend Mother’s code for what other people called “the spirit of Vatican II.” It took in a lot of territory. Susan drank coffee and put her cup down on the edge of Reverend Mother’s desk.

“My brother Dan straightened it out,” she said. “He called and rented it himself. I think he used a little pull.”

“Pull.”

“He’s the district attorney for the city of New Haven, Reverend Mother. And it is a local rental company. Local to New Haven County at any rate.”

“You should have joined an order with a Motherhouse farther away,” Reverend Mother said. “Maybe that was the problem. Usually, I think it’s better for women to be close to home, but in your case—”

A look passed between them, something that said they both knew everything there was to know about “this case.” And would rather not talk about it. Susan had a sudden, vivid memory of the day she had told Reverend Mother what had happened in her life. She had sat in this chair in her novice’s habit and talked for six hours.

Reverend Mother poured more coffee, which Susan knew she wouldn’t drink. Reverend Mother never drank more than one cup a day.

“Do you know what you’re going to do with yourself?” she said. “I can’t imagine you want to work for the district attorney’s office. I can’t see you as one of those new women lawyers with their suits and their athletic walking shoes.”

“I’d have to go to law school for that, Reverend Mother. And I don’t think Dan could hire me even if I wanted him to. They have rules about nepotism, you know.”

“How old are you?”

“Thirty-five.”

Reverend Mother nodded. “I think I’ve heard of your brother. There was a case, about two years ago. It was in all the papers. About child abuse in a daycare center.”

“That was Dan,” Susan said. “And it was certainly in all the papers.”

Reverend Mother shot her a strange look. “What’s the matter, Sister? Don’t you get along with your brother? The papers at the time made him sound like—well, like a crusading knight.”

“I like my brother just fine, Reverend Mother. I suppose I don’t know him all that well. He’s ten years older than I am. He’s never even been to visit me up here. I’m closer to the younger one.”

“Younger than you are?”

“A little.”

“And?”

Susan shrugged. “His name’s Andy. You may have seen him once or twice. He’s been up here on visiting days.”

“What does he do?”

Susan smiled. “Reverend Mother, the three of us were brought up with a lot of money. Sometimes, with people who have been brought up like that, it’s better not to ask what they do.”

“Meaning he doesn’t do anything,” Reverend Mother said.

“Meaning he thinks he’s an artist,” Susan said.

Reverend Mother sighed. “I think you should have taken that job with the archdiocese,” she said. “I know it was social work and you’re not trained for that, but you could have handled it. It would have made a good transitional phase. Halfway in and halfway out.”

“Except that sometimes it’s not so transitional, Reverend Mother. Sister Davida took a job with the archdiocese in 1972. She’s still there.”

“Nineteen seventy-two was a very different year.”

“An entirely different decade.”

“And Sister Davida was a very different kind of nun.”

“Reverend Mother, Sister Davida was a psychopath.”

Reverend Mother got out of her chair. She was a huge woman, tall and grotesquely fat, except that under the folds of a conservative habit nobody ever looked really fat. Just tented.

“Susan, Susan, Susan,” she said. “You’ve got to stop saying things like that. Seventeen years, and we didn’t even make you circumspect.”

“Maybe,” Susan said, “but I can recite the Litany of Loretto from memory. And I can recite the Miserere from memory in Latin.”

Reverend Mother turned away, opened the top drawer of her filing cabinet, and went rooting around for Susan’s papers.

In the seventeen years she had known this woman, Susan had never once seen her put anything in its place.

3

Fifteen minutes later, Susan climbed into the convent van next to Sister Mary Jerome, stuffing the things she was taking with her on the dashboard over the glove compartment. There wasn’t much. A dwarf manila envelope held her fifteen-decade rosary and the brown scapular she had worn under her habit. A larger manila envelope held a small packet of unopened mail. The Miraculous Medal she had worn around her neck was still there, under the shirt and sweater Dan had sent her. God only knew why.

Sister Mary Jerome sat in the driver’s seat, stiff and cold and disapproving. She was a young nun with an uncertain vocation and a sour face, a well of bitterness that could not be excavated because it had no bottom. Defections always threatened her.

She pointed to the manila envelopes and said, “If we go up a hill, that stuff is going to fall on the floor.”

Susan took the manila envelopes and put them in her lap. Sister Mary Jerome frowned at them.

“I can’t believe you aren’t going to open your mail,” she said. “I always open my mail. We only get it once a week.”

“And there’s never anything in it,” Susan pointed out.

“There’s a lot in yours.”

“It’s just circulars, Mary Jerome. Religious publishing houses wanting to sell me catechisms. Religious supply houses wanting to sell me First Communion gift sets. It’s because I was principal of a school.”

“You get mail every week,” Mary Jerome said. “I see it stacked up on the table in the living room. Sometimes I go months without seeing an envelope.”

“I’ll send you some,” Susan said. “I’ll even get my brothers to send you some. Don’t you think we ought to get moving?”

Mary Jerome turned the key and shifted into gear. “I can’t believe you’re not going to open your mail,” she said again. But she had pulled the van into the drive, and they were moving.

Through the windshield, Susan could see snow beginning to come down, white against the black bark of naked trees. Saint Michael’s had nearly two acres between it and the road. Standing on the porch at the front of the Motherhouse was like looking into primeval forest. The lawn could have been endless.

Today the drive itself was slicked with ice and looked dangerous. Mary Jerome was alternately humming the alleluia and muttering under her breath about �

�we.”

When they made the first turn of the three that led to the gate, Mary Jerome said, “Some people just don’t know how to appreciate that mail.”

4

Halfway to town, Susan finally opened her mail. She did it because she was nervous, and because Mary Jerome kept staring at it. Mary Jerome kept staring at her, too, but there was nothing Susan could do about that.

They were rolling along on ice and snow, going much too fast, skidding across streets that dipped and curved and plunged between white Protestant props. A Congregationalist church. A gambrel colonial built before the Revolution. Susan had never noticed before how deliberately picturesque this town was, as if a Norman Rockwell aesthetic had been imposed on it by legislation, from above.

“People just don’t understand,” Mary Jerome said. “About mail, I mean. I tell my family and I tell my family, but they just won’t listen. They think just because we’re not allowed to write more than four times a year, they shouldn’t write to us more than four times a year.”

“My family never wrote to me at all,” Susan said. “They certainly wouldn’t be writing now.”

“I think now was exactly when they’d write.”

“I don’t want to talk about it, Mary Jerome.”

Mary Jerome stared at the pamphlet Susan was unwrapping, glossy and four-colored and crammed full of pictures of the Virgin on a cloud, GOOD NEWS FOR CATECHISTS, was written across the top of it. “I would never have entered the kind of order where I’d be the one buying catechisms instead of Reverend Mother. I mean, why would I have bothered? What’s the point of being a nun if you’re going to run around in makeup and live in an apartment?”

Susan almost said: What’s the point of being a nun? But she had answers to that question, better ones than Mary Jerome had, and she could only have asked it out of spite.

She dumped the circulars back into their manila envelope and took out the only interesting thing, a small box wrapped in brown paper, the kind of box samples of toothpaste came in when you lived in a suburban house. It had been addressed by hand.

Mary Jerome eyed it, the envy plain on her face, turning her ugly. “Is that from one of your former students? If it is, it’ll be a tube of hand lotion. That’s what they always send. Scentless hand lotion.”

It wasn’t a tube of hand lotion. It was a five-decade rosary, made out of amber, a slightly more expensive-looking version of the kind of thing laypeople used when they said “a third part.” Mary Jerome’s eyebrows climbed up her forehead to the edge of her veil, making her look Neanderthal.

“Good Lord,” she said. “Who’d send a rosary to a nun?”

Susan closed her eyes and told herself: I am not a nun.

I.

Am.

Not.

A.

Nun.

Chapter Three

1

YEARS AGO, LONG BEFORE he was even old enough for high school, Pat Mallory used to come up to Edge Hill Road to see the houses. In those days, New Haven was a “nice” town, a half-city with an urban feel but a country rhythm. It was also solidly Catholic. With the exception of Yale, an Anglo-Saxon fortress spread out across Prospect and Chapel streets and tucked into the trees on the narrow offshoots of the business district, New Haven then might as well have been dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary. Maybe it had been. What he remembered most about those trips up the hill were the names on the mailboxes. Meehan, Carroll, Hanrahan, Burke: all those great stone houses, seven and eight and nine thousand square feet big; all those broad front lawns; all those long black cars; all of it, every piece of it, Irish. A year or two later, when Kennedy was inaugurated and the nuns at school opened every class by thanking God for putting a Catholic in the White House, Pat had thought he’d finally understood. Edge Hill Road was the kind of place people like the Kennedys came from.

Now, getting out of the car into the cold stiff wind of the dark December 2 morning, he half wished he were ten years old again. The great stone houses were still there, but they meant less to him than they once had. Everything did. Three abortive years on scholarship at a very expensive Jesuit college in New York had taught him that Edge Hill Road was not the kind of place Kennedys came from. It didn’t represent enough money, and it was too close to town. Seventeen years with the New Haven Police Department had taught him that New Haven wasn’t a very “nice” town, not anymore, and that it was getting less nice all the time. Lately he had begun to wonder why he was living in it. The neighborhood where he had grown up, with half a dozen brothers and sisters stuffed into seven rooms and a statue of the Virgin on the front lawn, was now a crack alley. The street in front of Holy Name School was lined with prostitutes. The Green was full of bums. Sometimes he felt like a science-fiction version of Rip Van Winkle: a man who has been asleep just long enough for his world to have turned into the antithesis of itself.

Still, it looked strange, a body stake here at the bottom of Edge Hill. Edge Hill might not be the kind of place Kennedys came from, but it was rich enough. There wasn’t a child on the street who went to a public school, and most of the girls “came out” in the most publicly possible way. Every spring, the backyards were full of striped caterers’ tents and dance bands imported from New York City. What they usually got up here was burglaries and breakins and driving-under-the-influence after nights on the town.

He slammed the door and waited for his driver to come around the car and join him. Now that he was chief of Homicide, he always had a driver, although he never had a car much better than the Buick unmarkeds he used to drive when he first got out of uniform. This driver was a boy named Robert Feld, still in uniform, black and much too young. Much too young. Sometimes the NHPD managed to sign on reformed street kids, hard boys who’d gotten religion, and they were always perfect. They knew the territory and they’d been leached dry of sentimentality in the womb. Robert Feld was the other kind. He had a degree from Storrs and a commitment to Positive Attitudes.

Pat let Feld come up to him, then pointed across the street. He looked away as he did it. Like most people, Feld made him nervous—because, like most people, Feld made him feel outsized. Pat Mallory was six feet six inches tall, two hundred and forty pounds, naturally bulked in the shoulders and naturally broad across the chest. He had never really worked out, because he had always been afraid to. In high school, he’d spent a year in mortal terror, convinced there was something wrong with his thyroid gland that was going to make him grow and grow and grow and never stop.

“Look,” he said. “Who caught this thing? They’ve got one of their lines tied to a lamppost.”

Feld blushed, then went patting around in his jacket pockets until he found a steno pad. He squinted at it. It was ten o’clock in the morning, but it wasn’t exactly light. The sky was crammed black with clouds. The streetlights, primed to turn off automatically every morning at seven, were giving off something like shade. It could have been the middle of a night when the moon was full, or the street was having a block party.

On Edge Hill Road, they didn’t have block parties.

Feld was getting into gear. “Conran and Machevski,” he said finally. “They’re who caught it.”

“They’re not Homicide,” Pat said. “Who do I have down here?”

Feld squinted again. Then he sighed. “I don’t know if I took this down right,” he said. “Ben Deaver. That’s right.”

Pat was sure it was. Ben Deaver was the highest ranking black in Homicide. He was also among the two or three smartest officers, of any color. Someday, soon, if Pat did twenty-five-and-out, Ben Deaver was going to have his job.

“The other one,” Feld said, “is a little fuzzy. Debero?”

“Dbro.” Pat sighed. “Jesus Christ.”

“Excuse me?”

“Never mind.”

“I’ve never heard of this—Dbro,” Feld said. “I’ve been driving you for five months, I’ve never heard of him. Is he new?”

“No,” Pat said. He looked acro

ss the street again. It was wide and deeply guttered. On any other day, it would have been choked with traffic. This morning it was choked with slush, a black river disappearing into blacker grates. The temperature was dropping again, just enough. In an hour or two, it would start to snow.

Pat left Feld where he was and crossed toward the line of police cars that had been parked to block the flow of cars and tourists. In the pocket of his jacket he had the note his secretary had written him after she’d taken the call that brought him down here: the first call, not the second. The first call was from Dan Murphy, the New Haven district attorney, the man in charge of media hype. He’d been on his way out of the office when that second one had come in. Now he wondered if he should have taken the time and answered the second call himself. It would have been Deaver, and Deaver always had something to say.

But the first call had been bad enough, even though it had been filtered through his secretary. He kept thinking about the note in his pocket and the fact that it would have to say now what it had said then. Dan was on the warpath, looking for a way to make the papers. That, coupled with Dbro, was the kind of disaster he did not need right before Christmas.

There was a body stake here at the bottom of Edge Hill Road, and the body staked had belonged to a nine-year-old boy.

2

Ben Deaver had taken his jacket and laid it across the hood of one of the black-and-whites. When he saw Pat coming, he picked it up and started to put it on. It was an automatic gesture, not meant. Pat shook his head slightly and Deaver put the jacket down again. Pat knew what was going on here, with Deaver at any rate. There were things you got used to after a while—things that, when you started out, held all the nauseating terror of the climax scenes in the horror movies you’d watched as a teenager. The things you did not get used to made you hot. Pat could remember himself in the back bedroom of that nursery school on Pinchard Street, looking at the pool of blood on the floor, at the smear of feces on the wall, at the cigarette butts clogging the drainhole in the sink. He had stripped off his jacket and his sweater. He had wanted to strip off his shirt. He had thought his skin was going to boil. Now, he thought, Ben Deaver was literally radiating heat.

Charisma

Charisma